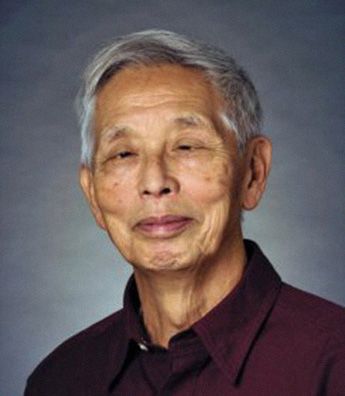

Tunney Lee was a professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and had served as chief of planning and design for the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

As an MIT professor, an architect, and an urban planner, Tunney Lee could look at buildings — particularly in Chinatown, where he grew up — and see much more than bricks and mortar.

“He could tell you about the history of the building, what organizations had been in the building, the families who lived there,” said Shauna Lo, a former board member of the Chinese Historical Society of New England. “He could tell you the histories of all the people and what they did for a living.”

A historian who was still at work on an extensive project to preserve the heritage of his childhood neighborhood, Mr. Lee died Thursday of complications from cancer treatment. He was 88 and lived in Cambridge.

A professor emeritus at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he formerly led the department of urban studies and planning, Mr. Lee had previously served as chief of planning and design for the Boston Redevelopment Authority.

He also had been deputy commissioner of the state Division of Capital Planning and Operations during the administration of Governor Michael S. Dukakis.

“I loved worked with him. He was a wonderful person,” said Dukakis, who over the years had lunch regularly with Mr. Lee and a small group.

“He was thoughtful, sensitive, committed, hard-working — I could go on and on,” Dukakis added. “He was great public servant.”

At MIT, Mr. Lee was a mentor to scores of architects, teaching them to look beyond the creativity that went into designing buildings.

“Architecture is a lifelong process. Design is an attitude of mind as well as a product,” he wrote when he was the founding chairman of the department of architecture at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Mr. Lee “influenced a whole generation of architects who were studying planning and architecture,” said Randall Imai, one of his former students who is now a principal at Imai Keller Moore Architects in Watertown.

“What he did was take our focus away from always creating beautiful objects and try to focus us on the purpose of the building and who it was going to serve,” Imai added. “It was really egoless architecture.”

While describing the Chinese University department he created, Mr. Lee wrote that his educational philosophy centered on “a basic concern for the quality of people’s lives and respect for all those involved in planning and creating buildings, including the people who will inhabit the buildings, coworkers, construction workers, as well as the owners, developers, and fellow colleagues.”

“To Tunney,” Imai said, “architecture was not an expression of personal talent, but rather a collaborative effort.”

Topper Carew, a filmmaker, architect, and longtime friend, said Mr. Lee believed that “people should be involved in making decisions about their space, about their architecture. It shouldn’t just be an ivory tower approach.”

Mr. Lee viewed the design process as “a tool to be used in the interests of citizen empowerment and citizen realization,” said Carew, who lives in Cambridge.

“That was his special gift. That’s rare,” Carew added. “For him, it wasn’t about building the buildings. It was about building the people.”

Tunney Lee was born in 1931 in Taishan, in the Pearl River Delta region of southern China. His father, Kwang Lien Lee, studied law in China and traveled with Mr. Lee – his son and oldest child – to North America.

Mr. Lee’s mother, Kam Kwai Chan, stayed behind in China with his three younger sisters. Because of the Chinese revolution, they were not able to move to the United States until decades later.

In an era when China was the focus of America’s strictest immigration quotas, men from that country were allowed to come and work in the United States. Mr. Lee was only 6 when he and his father left Taishan and, after crossing the Pacific, landed in Vancouver before crossing Canada on a train.

In Nova Scotia, they boarded a steam ship for Boston. Mr. Lee, who had turned 7 by then, stood at the ship’s railing gazing up at Custom House Tower as they sailed into Boston Harbor in 1938.

At the East Boston Immigration Station, immigration officers questioned Mr. Lee for nearly an hour.

“I don’t remember being scared, but I must have been,” he recalled in a 2010 Globe interview.

“I think of the memories of that building in terms of the people,” he added. “The ghosts. That period of America’s history and Boston’s history has been forgotten.”

While his father went to work in Washington, D.C., Mr. Lee remained in Boston, living with his grandparents — initially in a single room in Chinatown that lacked water or electricity. They bathed with water heated in a small pot.

During summers, he visited an uncle who ran a laundry in Barre, Vt. — “an avid hunter and fisherman,” Mr. Lee recalled in a 2009 interview with Lo, assistant director of the Institute for Asian American Studies at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Mr. Lee graduated from Boston Latin School and received a bachelor’s degree in architecture from the University of Michigan. He worked with the architect and futurist Buckminster Fuller, and for architect I.M. Pei.

While working for Pei in New York City, he met Irene Friedman, a University of Chicago graduate who was studying at Cooper Union. Mr. Lee wrote her love letters while he studied in Italy on a Fulbright scholarship until she joined him and they married in Rome, in 1957.

Mrs. Lee taught dance and later was a social worker in Boston. She died in 2001.

They had four daughters, the oldest of whom, Tevah, was a young girl when she died of leukemia.

Carew recalled that in 1968, Mr. Lee was “the head designer for Resurrection City” – the occupation on about 15 acres near the National Mall that was part of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.‘s Poor People’s Campaign.

Such experiences, along with his own childhood, informed Mr. Lee’s approach to his work.

“He was more interested in the sociological aspects of architecture,” Imai said.

A teacher wherever he was, Mr. Lee “looked at the world with an artist’s eye and an architect’s eye,” said his daughter Thea of Washington, D.C. Vacations regularly brought the family to Europe, where Mr. Lee, who “was extraordinarily warm and loving,” was especially fond of Italy.

“His life’s work was thinking about designing spaces that were welcoming and engaging and supportive of human activities,” Thea said. “Walking through a city with my dad was a wonderful thing. He marveled at the way humans used urban spaces.”

She added that “he loved cities, and he loved one city in particular, which was Boston. He used to say to me, ‘Everybody should know at least one city really well.’ ”

In addition to Thea, Mr. Lee leaves two other daughters, Kaela of Cambridge and Dara Lee Lewis of Brookline; three sisters, Mu Zhen Li of Braintree, Cui Yu Li of Quincy, and Xiao Xia Li of Newton; and three grandchildren.

The family is planning a Zoom service of remembrance.

Mr. Lee had spent years on the Chinatown Atlas, an ongoing project, which has a website that has been honored by the Massachusetts Historical Commission and which Imai and others hope to turn into a book.

In keeping with Mr. Lee’s multilayered consideration of any buildings, the project is “an anthropological atlas,” Imai said.

“Our role as citizens, I think, is important,” Mr. Lee once said in an MIT roundtable discussion on urban planning that is posted on YouTube. He added that “we should not be just technocrats building the site. We are citizens as well who care about things like quality and inequity.”

by Bryan Marquard